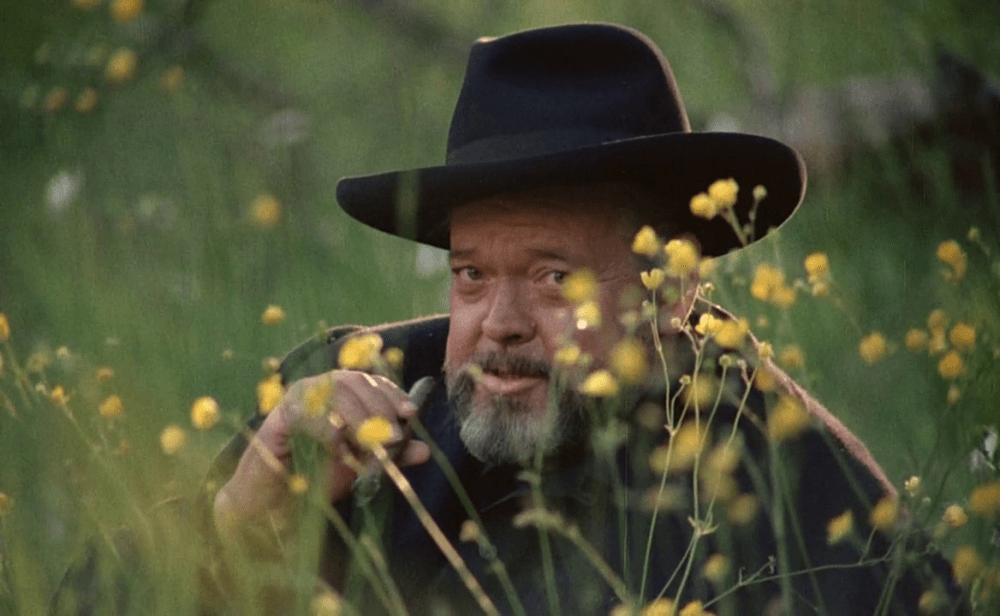

On F for Fake (1973)

Dir. Orson Welles – America – Docufiction

A classic work of docufiction by none other than Orson Welles, in his first of only two documentary films – although it’s arguable of just how much of this is documentary. Its surface questions the beauty of art and its relationship with true authorship, but deep down, I feel it is not only a manifesto, but a love letter to the magic of cinema. It oozes the magnetic charisma that Orson Welles himself does, and bombards you with incredible imagery in collage form.

Highly edited and tightly controlled as Welles reminds his audience regularly with an avuncular wink and brazen grin from the editing room. He sits behind the Moviola (!), and is flanked by an array of rainbow-coloured cans of films. Not dissimilar to what Chris Marker achieves in Letter from Siberia, wherein he consciously bestows the knowledge of “fakeness” of documentary upon you. It’s tailored perfectly for a man with as much of a mythos surrounding him as Elmyr. We don’t even particularly know if he was real at the end or not. I’d question the validity of Orson Welles being the director of the film if the whole thing wasn’t so slick and charismatic.

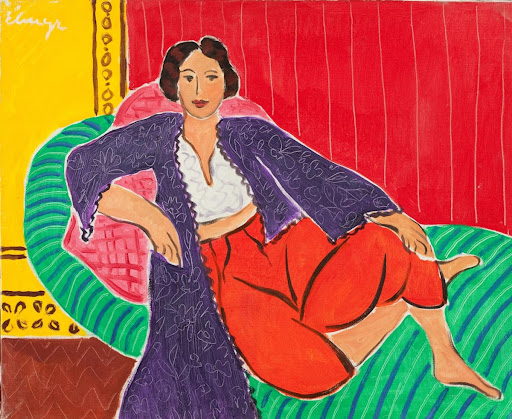

Art forgery really is the perfect crime. Is Elmyr not better than Modigliani if he can replicate his paintings without hesitation, as he puts it? Is he not Picasso’s equal, if he can move as deftly and confidently with each stroke of the pencil? The art world seemed to think so, whether they liked it or not. Perhaps it was not far away from the art dealer’s reaction when Elmyr had found one more Matisse “in his drawer” – not wanting to pry for further details. It’s like he said, it’s what everyone else does.

For all the questions of authorship the film raises, I’d ask: is forged or imitated art not as beautiful? The question of originality being the beautiful thing feels redundant to me. Within a culture or period, all art either seems to be a palimpsest of those who came before, and, if not, a conscious polarisation away from the contemporary schools of thought, and towards more “folk” renditions of subjects, or to theorise in the opposite direction of them. Even the impressionists were inspired by ukiyo-e woodblock printing and vaguely “oriental” art. Just because Elmyr imitates Modigliani, does it deprive his work of beauty? Demonstrably not. Not even for the expertise of so-called art scholars. Orson Welles made this documentary to show how the snobbery of the art world was a laughing stock to the rest of the world. How it was built on a sham. And to praise the world’s greatest conman. And perhaps one of the world’s greatest artists. A man who wore the hats of so many others. A man who took them for a ride and didn’t even care to make it known, or to make himself rich.

I’ve said it before and I’ll maintain my standing: editing is the most important part of documentary filmmaking. Anyone can point their camera at something that’s already happening – Herzog’s “truth of accountants”. Direct cinema, as filmmaking goes, is extremely easy to attempt. The real difficulty is making good vérité. F for Fake is far from the disciplines of direct cinema or vértié, but it certainly harbours elements of it on the surface, although really it is an audio decoupage. It’s mostly an expository essay, but has traits of reflexive and participatory documentary. Large swaths of the runtime are dedicated to conversational dialogue at parties, which, if staged, are nothing short of mastery of realism, or, if they aren’t, are an expertly documented capture of the subjects. These are perfectly complimented by the staged, scripted sections of narration Welles delivers himself. Conversations that occur between people speaking, unscripted, from different days, and in different locations, become scripted. They interrupt one another naturalistically, stepping on each others’ toes, completing each others’ sentences, and reply to Welles, a third participant, commenting from his editing booth. They find themselves among fast montages of members of the public, working for free, as Welles puts it at the start. We see the montage and the conversation as distinct, but the pictures of crowds, as the words of Elmyr de Hory and Clifford Irving, are all the same medium to Welles’s edit. They are material to be used to prove his point. To prove it’s all trickery. He can paint with words as he can paint with pictures, and it doesn’t matter what they said or what the stock footage looked like before, because it’s part of his illusion now. Blended to be seamless.

Welles manages to throw his own mythos and personal history in for the audience too, just in case you were in doubt of the authenticity of the film’s content. Maybe this is really his manifesto, and that the magic of entertainment, by theatre, by radio, or on the silver screen, is all the same. He censors his War of the Worlds broadcast audio by rerecording it as preposterous and hackneyed as can be, and follows it by describing the turmoil that the nation plunged into in reaction to its airing, which, although real, does it now not sound totally implausible? Or does it bring credibility to the obviously faked audio? The real answer to both questions is a third: were you not entertained? It truly does not matter which thing was genuine and which was not. The conversations between Elmyr and Irving didn’t happen that way, and we didn’t care then – why bother to care when it comes to the art rather than a conversation? No expert with their lens of objectivity can enjoy the kaleidoscopic interpretations of art and the emotive power it is bestowed with. No matter if the audio was altered or remains the same, it is entertaining.

Cinema is a haunted medium: reanimating the same grains of film of men long dead, showing them to be doing things they never really did, showing magicians pretending to be real people, showing fantasy to be their reality. It’s to emote. To experience. To feel.